Abstract: Computational Law (aka Complaw) is a branch of Legal Informatics concerned with the automation of legal analysis. While the idea of automated legal analysis is not new, it is becoming increasingly practical due to recent developments in information technology. Computational Law has the potential to dramatically change the legal profession, improving the quality and efficiency of legal services and possibly disrupting the way law firms do business. More broadly and more importantly, Complaw has the potential to bring legal understanding and legal tools to everyone in society, not just legal professionals, thus enhancing access to justice and improving the legal system as a whole. And, of course, Complaw is essential for the proper functioning of autonomous systems (such as self-driving cars and robots). 1. IntroductionAround 1750 BC, The Babylonian king Hammurabi mandated that the laws of the land be encoded in written form (literally cast in stone) so that citizens could know what was expected of them and what would happen if they violated those expectations. In his own words, he wanted "to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land ... so that the strong should not harm the weak".

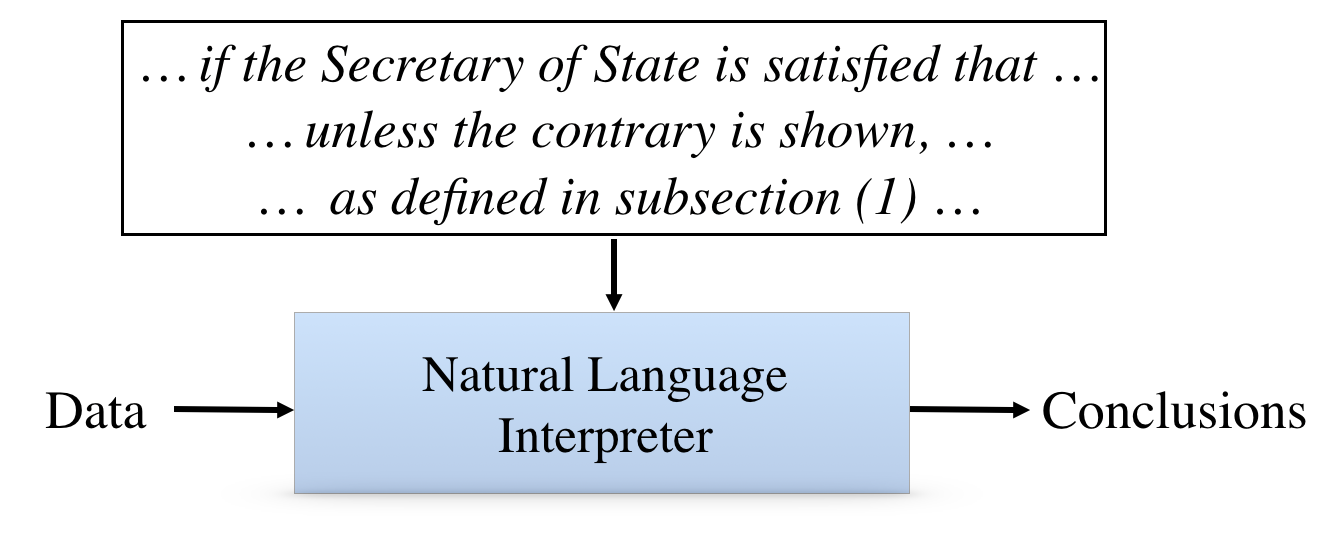

Today, we live in a complex regulatory environment. We are subject to governmental regulations from multiple jurisdictions. In the United States, there are federal regulations and state regulations and local regulations. The sheer number and size of regulations can be daunting. We may all agree on a few general principles; but, at the same time, we can disagree on how those principles apply in specific situations. The Declaration of Independence is an important document in American history. It outlines the principles on which the country is based in just 1322 words. By contrast, the regulations on the sale of cabbages alone reputedly run to 26,911 words. That's not bad writing. The number and size of the regulations is essential to deal with specific issues and special cases. Complicating the situation is the complexity of these regulations. Even small regulations can be very complex. Moreover, once regulations are created, complexity often increases as they are changed and then changed again. Here is an example in the context of insurance. A few years ago my house suffered some damage from flood water. Looking at page 32 of my insurance contract, I was pleased to see that water damage is covered. Unfortunately, when I called my insurance company, the adjustor pointed out the qualification on page 112 stating that the coverage on page 32 does not apply when various conditions exist "due to flood water". Policies likes this are typical in the insurance industry. And they are difficult for most people to understand without specialized legal knowledge or at least a substantial amount of study. To make matters worse, regulations are not always well coordinated, arising, as they do, in different settings for different purposes. Sometimes, there are gaps, leaving important cases uncovered. More often, regulations overlap other regulations and in some instances are inconsistent with each other. These problems make it difficult for affected individuals to find and comply with applicable regulations. The result is occasional lack of compliance, widespread inefficiency, and frequent disenchantment with the regulatory system. This is a failure of our legal system. One of the functions of the law is to help individuals predict the consequences of their actions. If we do not know what the law is, the law does not serve this function; and, as many people have observed, the law today is far too complex for people to understand fully. Lee Loevinger captured the irony of this situation in an article written in 1949: "It is one of the greatest anomalies of modern times that the law, which exists as a public guide to conduct, has become such a recondite mystery that is incomprehensible to the public and scarcely intelligible to its own votaries." 2. Computational LawAll is not lost. These problems are not insurmountable. They are information processing problems; and as such, they can be mitigated by information technology. What is needed is appropriate "legal technology" - information technology applied to laws. One step in this direction has already been taken. Today, the text of many legal documents is available online. In some cases, the information is adorned with "semantic" keywords to help in search. The good news is that these documents can be found using general search services, such as Google, or using services that specialize in legal information, e.g. those provided by companies like Westlaw and LexisNexis. Unfortunately, the quality of such search is limited. They often return too many documents, and sometimes they fail to find relevant documents. More importantly, there is no technology for interpreting these documents; human specialists must still be there to read the documents and apply them to individual cases. An alternative, the subject of this article, is an extreme form of legal technology known as Computational Law (Complaw). Computational Law is that branch of legal informatics concerned with the automation of legal analysis. Not just legal search but legal analysis. Not just documents, but answers. And not just guesses with frequent hallucination but reliable answers. There are multiple opportunities for computational law in our current legal system - in adjudication and in regulatory analysis and rule-making. However, there is a more immediate application, viz. compliance management, i.e. the development and deployment of computer systems capable of assessing, facilitating, or enforcing compliance with rules and regulations. Intuit's Turbotax is an oft-cited example of a compliance management system. Millions in the United States use it each year to prepare their tax returns. Based on values supplied by its user, it automatically computes the user's tax obligations and fills in the appropriate tax forms. Turbotax illustrates some of the key advantages of Computational Law for the individual. (1) It embodies tax regulations in computable form. (2) And it does its work in a situated fashion, not in the abstract but rather in the context of the user's circumstances, thus teaching the user about relevant regulations in real world setting. Of course, taxes are not the only application of Computational Law in compliance management. There are many other areas of the law that are amenable to similar treatment. Portico is a prototype of a system developed at Symbium for assisting architects and homeowners in formulating architectural designs that comply with planning codes and building codes. Analogous systems have been built in other areas - e.g. management of child support, immigration aids, building inspections, and so forth. Moreover, the regulations implemented in Complaw systems are not restricted to governmental rules. They can equally well be the policies of universities and corporations (e.g. travel expense reimbursement, product configuration worksheets, and pricing rules). Students at many universities use academic planning worksheets to choose courses that fulfill all program requirements. (a) Such worksheets show all requirements explicitly. (b) They calculate units in accordance with departmental policies, ensuring no double counting. (c) They ensure that all prerequisite classes are taken. (d) They prevent students from taking mutually exclusive courses. And so forth. There are also applications that are not based on governmental laws or institutional requirements. The rules and regulations can just as well be the terms of contracts (e.g. insurance covenants, delivery schedules, real estate transactions, financial agreements). 3. TechnologiesSo much for overview. Time now for some details. Let's start with a look at technologies. How do we build Complaw-enabled compliance management systems? Obviously, compliance management systems need data. The good news is that there is vast and daily increasing amount of data online in the form of tables in relational databases and in the form of knowledge graphs. In addition there is the data supplied by users of interactive forms and design tools like the ones we mentioned earlier. The question is how to build systems that can analyze this data from a legal point of view. There are a variety of possible approaches. One approach to building such systems is natural language processing (NLP). There are optimists who think that we can use of NLP to interpret texts of rules and regulations. The basic idea is good. Unfortunately, it is not practical for a couple of reasons.

First of all, today's natural language processing technology is not very reliable. It is great for use by computer assistants in understanding simple command, like setting timers. Unfortunately, it is not so good at understanding more complex information. Henry Kautz, the director of the Computer Science office at the National Science Foundation recently shared a good example. He was listening to Barber of Seville and reading Google's translation of the libretto. At one point, he noticed this curious translation shown in the subtitle: "Dunkin Donuts indeed". Now, I do not speak Italian, but I am pretty sure that that is not what Gioachino Rossini intended. Unfortunately, the drawbacks of this approach are not entirely due to limits of our current technology. There is a deeper problem. The fact is that natural language is inherently ambiguous, as illustrated by this sentence: There is a girl in the room with a telescope. Is the girl in the room that has a telescope or is there a girl in the room and she is holding a telescope? There is no way to know for sure without significant context.

Such complexities and ambiguities can sometimes be humorous if they lead to interpretations the author did not intend. See the examples below for some infamous newspaper headlines with multiple interpretations. Using a formal language eliminates such unintentional ambiguities (and, for better or worse, avoids any unintentional humor as well).

As an illustration of errors that arise in reasoning with sentences in natural language, consider the following examples. In the first, we use the transitivity of the better relation to derive a conclusion about the relative quality of champagne and soda from the relative quality of champagne and beer and the relative quality of beer and soda. So far so good.

This makes sense. It is an example of a general rule about the transitivity of the better relation. If x is better than y and y is better than z, then x better than z.

Now, consider what happens when we apply this rule in the case illustrated below. Bad sex is better than nothing. Nothing is better than good sex. Therefore, bad sex is better than good sex. Really?

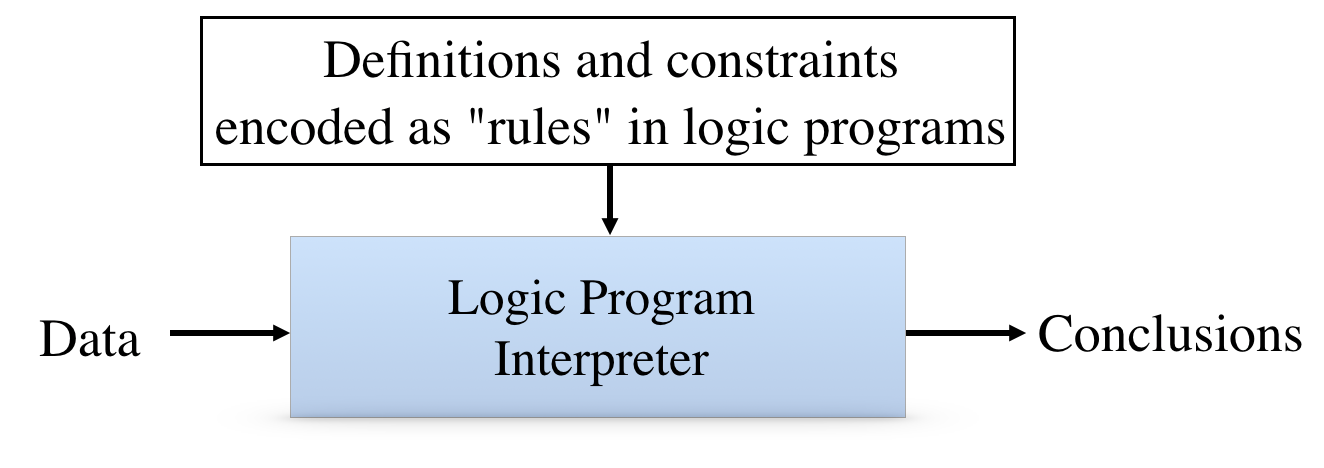

The form of the argument is the same as in the previous example, but the conclusion is somewhat less believable. The problem in this case is that the use of nothing here is syntactically similar to the use of beer in the preceding example, but in English nothing means something entirely different. A better approach is logic programming. In this approach, we encode information in the language of Symbolic Logic. Using this language, we can define new concepts; we can state physical constraints; and we can encode rules and regulations. A grandparent is a parent of a parent. Parents are older than their children. And people may not permitted to be married to two different people at the same time. Like natural language, the language of Logic is expressive; yet, unlike natural language, it is grammatically simple and unambiguous. Moreover, we know how to build interpreters that can reliably derive conclusions from data and rules.  The good news is that we can use these interpreters for multiple purposes. Consider the corporate definitions and rules shown below. Officemates are people who share an office. Managers and subordinates may not be officemates.

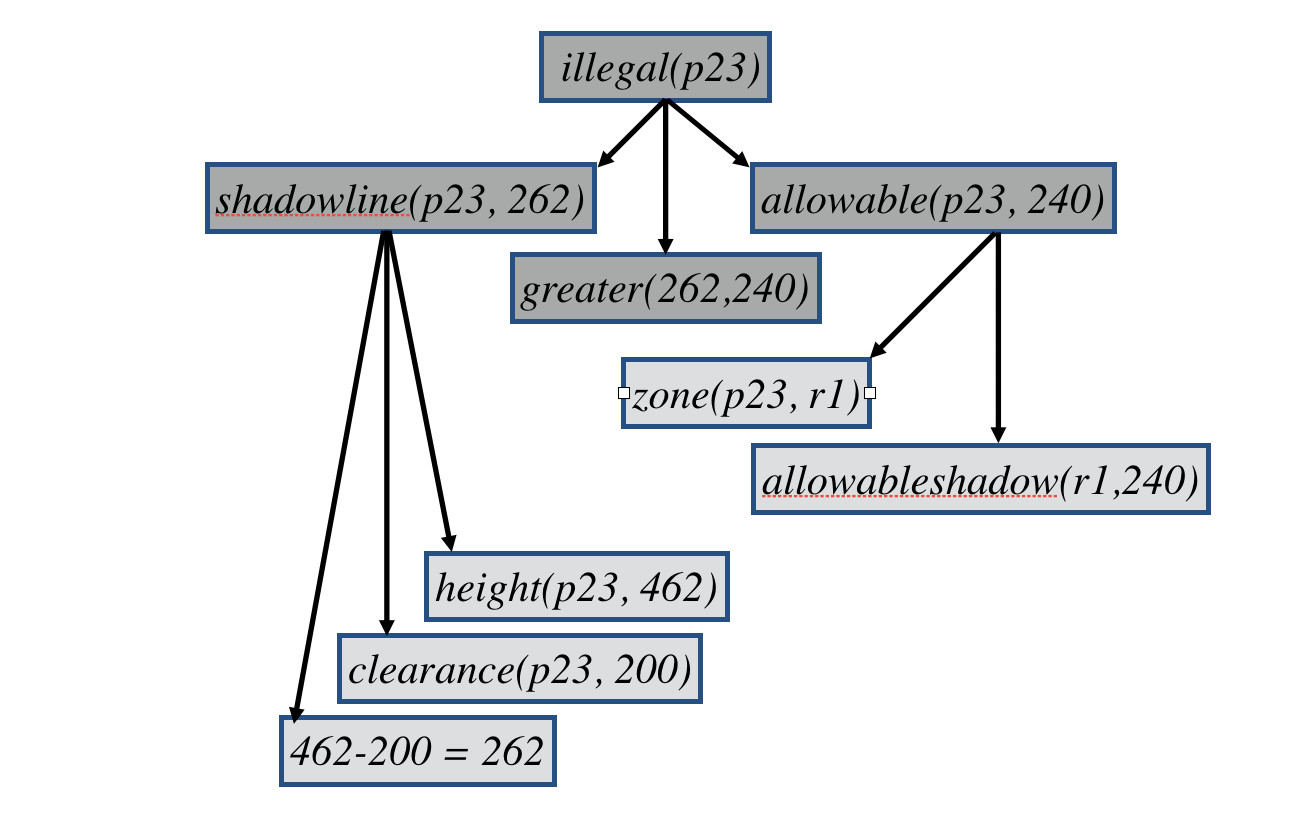

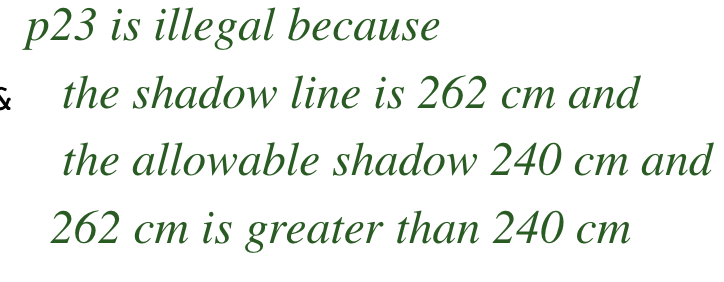

Using just this information, it is possible for a logic program to check for compliance checking. For example, if John manages Ken and John is in 22 and Ken is also in 22, it is easy to detect the violation. A logic program interpreter can also be used to plan for compliance planning. In this same situation, if John manages Ken, then the system can suggest room assignments that do not violate the regulations. And a logic program interpreter can also be used for inconsistency detection among policies. Managers and subordinates should not be in the same room, and all skunkworks personnel must be housed in the same room. If John is the manager of skunkworks and ken is an employee, then the second sentence above tells us he cannot be in the same room as Ken while the third sentence tells us he must be in the same room. But wait, there's more. Things do not necessarily end with the derivation of answers. Such systems can also give users explanations. In deriving conclusions, LP systems can generate derivation trees for those conclusions; and it is possible to generate sensible explanations by incrementally presenting those derivation trees to the use. The example here comes from the Portico system mentioned earlier.

Using this derivation tree, the system can explain why the building plan was rejected by citing the actual shadow line of the building and comparing it to the allowable shadow line.

If asked, the system can go one step farther and explain the actual shadow line and the allowable shadow line. There are subtleties in explanation, but this approach renders comprehensible and accurate explanations relatively easily. 4. ChallengesOkay, so much for the good news. Now for a look at some of the difficulties, the challenges in using logic programming or, for that matter, any other approach to building compliance management systems. One technical problem, familiar to many individual with legal training, is open texture. Consider a municipal regulation stating "No vehicles in the park". On first blush this is fine, but it is really quite problematic. Just what constitutes a vehicle? Is a bicycle a vehicle? What about a skateboard? How about roller skates? What about a baby stroller? A horse? A repair vehicle? For that matter, what is the park? At what altitude does it end? If a helicopter hovers at 10 feet, is that a violation? What if it flies over at 100 feet? The problem is that the words used to define this rule do not have precisely defined meanings. Why not make the rule more precise by defining the notion of vehicle precisely?  There are good reasons that such problems arise. In some cases, rules are stretched by changes in technology, e.g. motorized skateboards in our example. More generally, we might expect to see problems with other laws due to technological changes like reusable rockets, autonomous cars, gene editing - developments that strain the rationale for the rules on the books. In some cases, concepts are left ambiguous intentionally, in order to make it possible for politicians and regulators to compromise, effectively "kicking the can" down the road for other regulators and courts to deal with. Even when the concepts are well defined, there are often exceptions to our rules. Consider a woman slightly exceeding the speed limit while driving her brother to catch a train. Or what about a husband driving his pregnant wife to the hospital? We might be willing to let minor infractions of this sort go. So why not make that part of the law rather than treating such cases as exceptions. There are several reasons for this. There may simply be too many possibilities to consider. And enumerating the exceptions makes for a very complicated legal code. And, of course, there are lots of unanticipated situations. Legislation as social programming. Of course, if law-making bodies and regulators did their jobs, there might be less need for legal debugging. A good program needs less debugging. Better laws might lead to less litigation. However, there are good reasons for not trying to deal with all cases in advance. Adjudication as legal debugging. The good news is that, in common law countries, like the US, we have mechanisms for dealing with such situations. We have judges and courts to hear specific cases, to deal with ambiguities and exceptions and to further refine laws and regulations accordingly. And we have appeals courts and in the US, a supreme court to ensure that they do it right. From a computer science point of view, the job of these judiciary bodies is to deal with ambiguities and exceptions. They are, in effect, debugging and, through the power of precedent, repairing deficiencies in the law. By the way, providing technological help in these areas is another possible application for computational law. In the not too distant future, we might see automated or at least semi-automated adjudication - not just applying logical rules but also modifying or elaborating rules to handle specific cases. And, someday. we may even be able to help rule makers by introducing automation into the regulatory process itself, analyzing propose rules and regulations, and maybe even recommending options that cover more cases from the outset and thereby eliminate the need for adjudication after the fact. Of course, if we want to automated legislation and adjudication, there are factors that must be taken into account when formulating or revising revising rules and regulations that do not apply when simply following rules. For example, we need some idea of what it is that people want, what matters to them. And we need some sort of policy on equity. Are we simply optimizing overall societal utility or do we also care about balancing the utilities of the different members of society in equitable ways? Also, adjudication and legislation need something more than logical reasoning / deduction to deal with cases where there are no unique answers. In the words of Edwina Rissland: "Law is not a matter of simply applying rules to facts via Modus Ponens", and when regarding the broad application of AI techniques to law, this is certainly true. The rules that apply to a real-world situation, as well as even the facts themselves, may be open to interpretation, and many legal decisions are made through case-based reasoning, bypassing explicit reasoning about laws and statutes. We do not at this point have adequate technologies for dealing with these matters. However, that does not mean that we cannot deploy compliance checking systems and reap the benefits. Just because a set of laws is not perfect does not mean that there is no value in informing citizens and organizations about the implications of the laws we have on the books. There is an analogy here between laws and our theories of the physical world. Classical (Newtonian) Mechanics tells us about the results of applying forces to objects. We teach it to our kids. We use it ourselves. Of course, classical mechanics is wrong. Nevertheless, we use it in 99.99% of our daily lives and for the other .01% we have specialized techniques. Despite the fact that it is not 100% correct, it is a useful approximation. In the case of the law, when we observe failures, we luckily have court systems to deal with those cases. 5. ImplicationsAt this point , we do not have adequate technologies for dealing with these challenges. However, that does not mean that we cannot deploy deductive compliance management systems and reap the benefits. Just because a set of laws is not perfect does not mean that there is no value in informing citizens and organizations about the implications of the laws we have on the books. (1) Embedded Law. The potential for deployment of such applications is substantial due to technological developments like the Internet, mobile systems (such as smart phones and smart watches), and the emergence of autonomous systems (such as self-driving cars and robots). All of which allow us to make automated compliance management tools available to citizens in their daily lives. Suppose that we had the benefit of a friendly policeman in the backseat of our car whenever we drove around (or perhaps an equivalent computer built into the dash panel of our car) - a cop in the backseat. The car can and should offer regulatory advice as we drive around - telling us speed limits, which roads are one-way, where U-turns are legal and illegal, where and when we can park, and so forth. The Cop in the Backseat. But a friendly cop rather than a punitive one. Maybe we should instead consider the possibility of a "Lawyer in the Backseat" or a "Driving Instructor in the Backseat". Capabilities like this already exist to limited extent in aviation, where displays like this one provide feedback on restricted areas and areas with special requirements (these concentric circles).

On the Internet when we are deciding whether to buy that drug from Canada or ship that alcohol to Virginia. This makes lots of things possible. Suppose you are walking through the woods of Massachusetts and you see an attractive flower. You take a photo with your iPhone. Your plant identification app identifies it as a type of orchid and lets you know. At the same time, your legal compliance app tells you that, no, you may not pick it. Unless you cross the state line to a neighboring state. (2) Automated Enforcement. A second implication is in area of automated enforcement. Technology makes it possible for us to enforce laws in ways that were not previously feasible. Automated reporting and billing is one potential of technology. Red Light cameras are examples. But there are also more interesting possibilities. Regimented systems, g.g. apple's photo policy. Enforcement technology might someday invade our own devices. Suppose that the cop in the backseat were not a friendly cop but instead a cop with the power to ding us for violations of the law. In the case of a computerized policeman with an internet connection, we could imagine the policemen immediately reporting the violation to the DMV (Department of Motor to Vehicles). Insurance companies already make devices that track and report driving performance, allowing conservative drivers to benefit from lower rates and increasing the premiums for more aggressive drivers. Taking this one step further, we can imagine cars showing the results of such reporting to their drivers as well other performance factors. The cars could display not just actual speeds, but also speed limits, DMV fine balances, insurance premiums, and so forth. It would be interesting to see the effects of such reporting on drivers. Would they drive more conservatively when they see their bills mounting every time they exceed the speed limit?  It seems clear that there are positive features to possibilities like these. They promote safety while enhancing efficiency. At the same time, there are concerns, e.g. whether it is equitable to discriminate on the basis of personal characteristic, whether automatic DMV reporting compromises our right to privacy, and so forth. On hearing about these possibilities, people often say "No way, no how. It will never happen." Maybe so. The question is whether it should. Is it a good idea or a bad idea? If it is a good idea, how can we help to make it happen? And, if it is a bad idea, how can we prevent it from happening? (3) Technology-Enabled Law. A third implication is what might be called technology-enabled law. We already have speed limits based on location, typically based on the lane of travel. Speed limits based on time of day are quite common.

What about speed limits based on the type of vehicle. Trucks are required to drive more slowly than passenger vehicles for reasons of safety. Perhaps Ferraris should be permitted to drive faster than Cadillacs because they are safer at higher speeds.

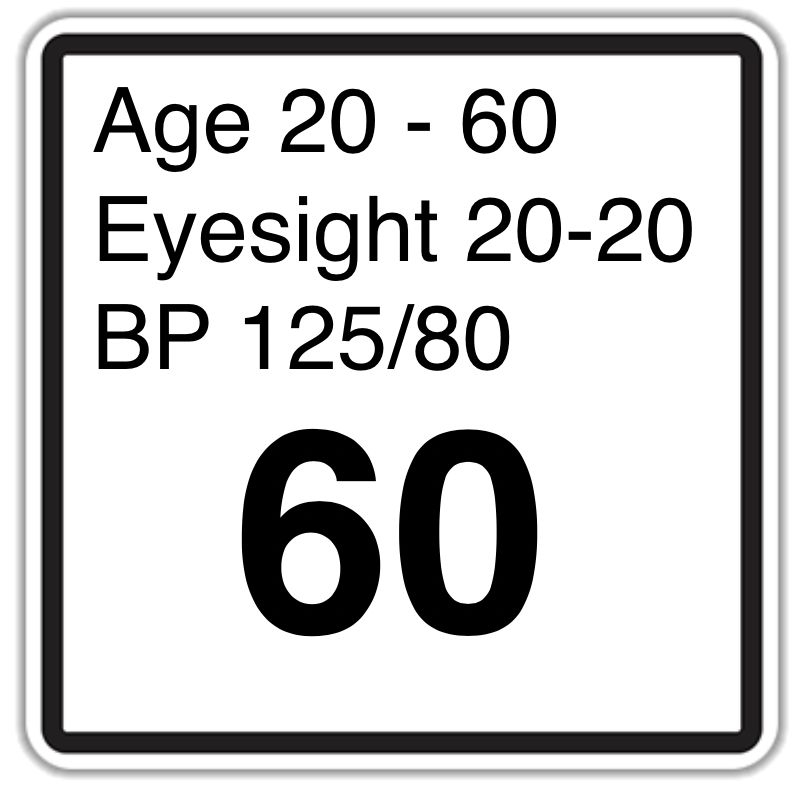

And what about speed limits based on personal characteristics, say age, or eyesight or blood pressure or other factors.

The Federal Aviation Administration already does this, disallowing individuals with poor eyesight from doing commercial flights. Vaccinations? 6. ConclusionThis article began by citing the information problems posed by complex legal codes and by suggesting that Computational Law may offer a solution and, in particular, the application of computational law to compliance management. Although there are still challenges to automated compliance management, there is value in deploying this technology. Embedded Law. First of all, there is embedded law - building law into the devices we use to interact with each other and with the world. Complaw technology has the potential for democratizing the law. It takes law out of the courtroom and the law office and makes it available to the people it is designed to serve. It makes the law available to ordinary decision makers at the point of decision, when they are about to act or planning how to act. It can alert people to obligations and restrictions; it can help people avoid mistakes of omission and commission; and it can help them get their due from the government, from insurance companies; and so forth. Equitable Enforcement. Second, this technology can decrease random enforcement, ensuring that laws are obeyed and eliminating the common frustration that result from being penalized for something when others go free. Better Laws. And there is a broader implication as well. Earlier we saw that complexity is one of the problems of our legal system. Such complexity is inherent in translating general principals into practical form, going from standards to rules. The fact is that there is virtue in complexity. We need it to cover all of the cases without resorting to one-size-fits-all rules. But there is also harm in complexity. Complexity is the enemy of understanding. The use of computational tools allows us to reap the benefits of complexity without the harm. It allows us to make better laws. Hammurabi and his predecessors began a lasting tradition. Over the centuries since those early legal codes were written, it has been the norm to encode rules in written form and disseminate those rules - first via stone tablets, then via books, and more recently via the internet. However, just writing things down and making them available is not enough when the laws are voluminous and difficult to understand. By automating legal reasoning, Computational Law fixes this. It facilitates compliance; it improves enforcement; and it allows us to have better laws. It is the natural next step in the development of our legal system. About the AuthorsMichael Genesereth is a professor in the Computer Science Department at Stanford University. He received his Sc.B. in Physics from M.I.T. and his Ph.D. in Applied Mathematics from Harvard University. Prof. Genesereth is most known for his work on computational logic and applications of that work in enterprise computing, computational law, and general game playing. He is the current director of the Logic Group at Stanford and founder and research director of CodeX (The Stanford Center for Legal Informatics). Robert Mahari is Robert Mahari He is an associate director of CodeX (The Stanford Center for Legal Informatics). |